Everyone has something that impacts their life. Something so profound and positive that, over time, you realize why it came into your life when it did. In this instance, a competitive sport developed into a deeper meaning for this amazing woman we're about to talk about. And how her love for running evolved into a powerful connection to the land she grew up on.

Running has always been Blaire Maryboy-Bitsinnie's passion. It became her constant growing up on the Utah strip of the Navajo Nation. The thrill of running across rocky mesas and toward Jóhonaaʼéí (the sun) every morning became a comforting childhood feeling that gave her a deeper appreciation for the world around her. There was no hard concrete, no gray skyscrapers, and no one else to compare herself to - only dirt roads and miles upon miles of desert home. She didn't learn to control her breathing, maintain her stride, or track her time in a gym or well-equipped facility - she learned these methods in the comfort of the land she knew all too well. Running provided her with a balanced spirit, mind, and physical state of being - what Navajos refer to as hózhó (harmony) - and ultimately allowed her to use it as a positive drive in her life.

Over the years, her passion transpired into a sport she continually excelled at. Throughout high school and college, she ran cross country and track, starting at Whitehorse High School, where her teams won region titles and competed at state meets. She then continued her running career at Diné College, where she accepted a running scholarship and secured a spot on their renowned cross country team. Her academic journey eventually led her to transfer and graduate from Fort Lewis College with her Cellular and Molecular Biology degree. About this move, she stated, "Even if Durango isn't that far from the reservation, I wanted to be closer to home" - a notion that most, if not all, young Indigenous adults can relate to.

Over the years, her passion transpired into a sport she continually excelled at. Throughout high school and college, she ran cross country and track, starting at Whitehorse High School, where her teams won region titles and competed at state meets. She then continued her running career at Diné College, where she accepted a running scholarship and secured a spot on their renowned cross country team. Her academic journey eventually led her to transfer and graduate from Fort Lewis College with her Cellular and Molecular Biology degree. About this move, she stated, "Even if Durango isn't that far from the reservation, I wanted to be closer to home" - a notion that most, if not all, young Indigenous adults can relate to.

As an only child, she valued her close relationship with her parents, and being raised with Navajo beliefs, she wanted to be within driving distance of everything she knew. Blaire wanted to be near her home in Red Mesa, Utah, and her family in San Juan County, Utah. She longed for the comforting feeling and energy of home - the people, the language, the culture, and most importantly, the land. "My family is rooted in San Juan County, and we are generations of Diné who are proud of our land and culture." The thing with young Navajos is they're taught that home is where their roots are planted, and it's stressed to always return home and reconnect. And this is what Blaire did every time she went home. She developed a love for the land because of family, culture, and running.

She elaborated that her grandparents emphasized the importance of always returning home. "With my paternal and maternal grandparents, I was taught to respect the earth, trees, the land - where you come from because you eventually go back. So in that retrospect, you adhere to the unspoken rule: you don't take more than you're given, you don't abuse it." When she harvested from the Bears Ears landscape, she learned how much to uproot without taking more than she needed. "We, as Diné people, see the land as being holistic. We're able to gather roots, gather herbs, gather even the dirt, the soil, and we use them in our planting and our traditional ceremonies. And all of this was used for our minds, our culture, our home - and if there's any disruption, it can interrupt that progression of life."

She elaborated that her grandparents emphasized the importance of always returning home. "With my paternal and maternal grandparents, I was taught to respect the earth, trees, the land - where you come from because you eventually go back. So in that retrospect, you adhere to the unspoken rule: you don't take more than you're given, you don't abuse it." When she harvested from the Bears Ears landscape, she learned how much to uproot without taking more than she needed. "We, as Diné people, see the land as being holistic. We're able to gather roots, gather herbs, gather even the dirt, the soil, and we use them in our planting and our traditional ceremonies. And all of this was used for our minds, our culture, our home - and if there's any disruption, it can interrupt that progression of life."

The correlation between Blaire's story and Visit with Respect's work is that the connection to the land is why we want to be respectful of it. The land is a living embodiment of restoration and healing. Every Tribe that ties their lineage and ancestry back to Bears Ears has many honorable reasons why emphasizing that every visitor must visit with respect. Blaire states, "You don't want to go out of your way to desecrate the land or make it known that you were there." Impacting the landscape is inevitable, but Visit with Respect's work and stories like Blaire's can help limit the destruction of cultural structures, water, valuable plant life, and soil.

Because of Blaire's background in the medical laboratory field, her work has included dissecting animals and exposure to cadavers - which are taboo in Navajo culture. "In my profession, I deal a lot with bodily fluids, like blood and body parts that I need to get biopsied or tested," Blaire states. To counteract these, she has ceremonies and prayers done, which include environmental resources found on the Bears Ears landscape. She continues to give her prayers and songs back to whatever she may be interacting with and restore harmony within herself. "I have medicine women and men who bless me, so I don't carry that negative energy back home with me." Although she's adapting to the modern-day world, she still carries thousands of years of tradition to help protect her, including the land's healing resources.

The land is alive and still giving back to people like herself. She highlighted how being outdoors and seeking the earth's healing properties can help restore an unbalanced person. "My dad used to tell me when I was in college that if you're ever feeling alone or afraid, you can go to your nearest tree and hold the branch, and know that life is going through it because it's growing." Every living thing in this world is rooted to the earth, so being out on the land helps reground you. And this type of practice gives a brief but accurate explanation of being aware of interacting with the environment. "You can feel the energy from the earth, the trees, and the branches - you can harness that energy and use that to move yourself into a positive direction, even if you're having a bad day." When it came to the topic of trying to mediate the degradation of the resources on Bears Ears, she said, "Educating visitors is the first step toward protecting the future." An Indigenous poet, Joy Harjo, said in one of her poems, "Remember the plants, trees, animal life all have their families, their histories too. Talk to them, listen to them. They are alive poems," and this notion is true to the work Visit With Respect hopes to continue educating visitors about.

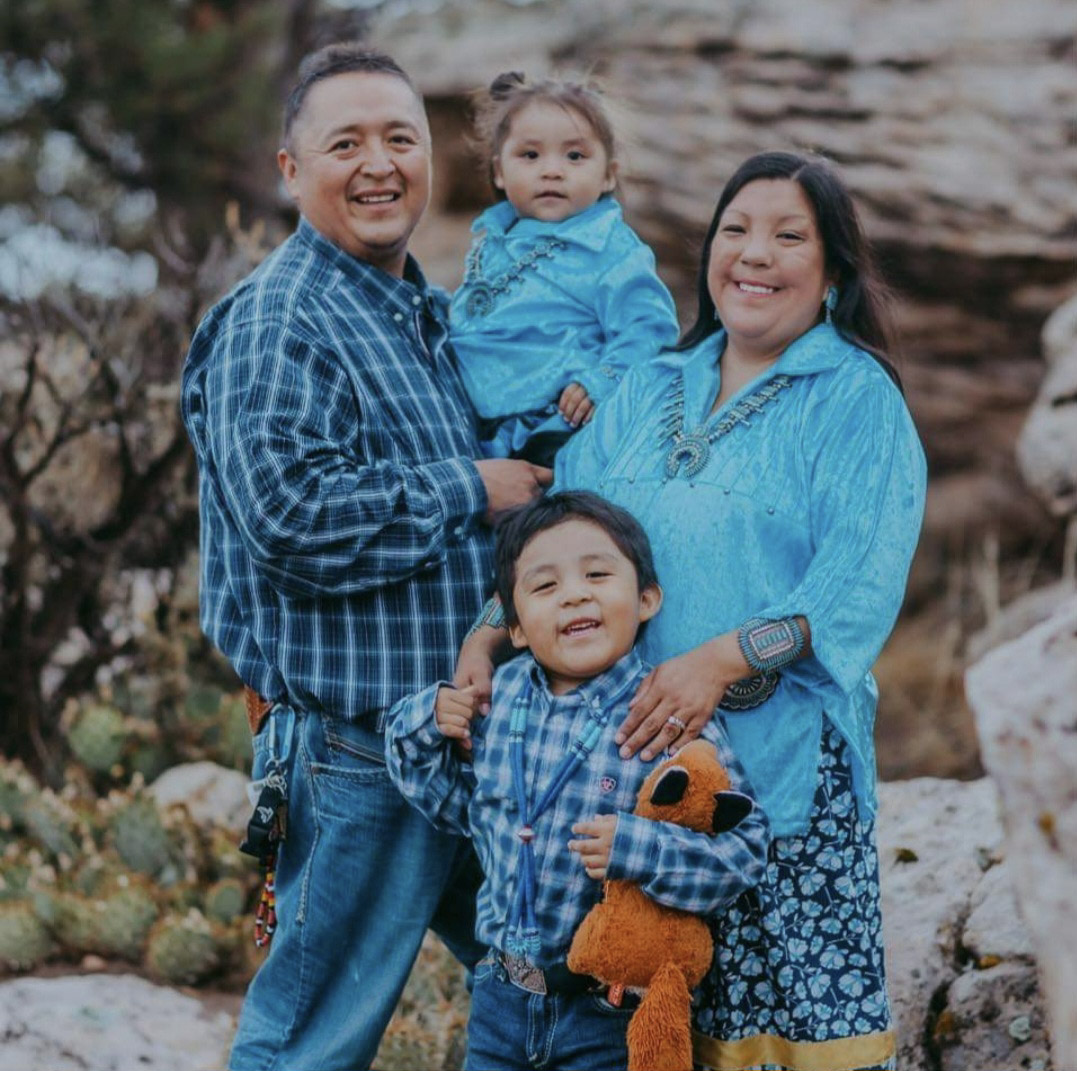

As for Blaire, the combination of running and her homeland inspired her to continue her journey. For a few years, she was the cross country coach at Whitehorse High School, where she started her running career. She passed the torch from one competitive runner to the next - giving knowledge and expertise the next generation can carry on. She currently resides in Red Mesa, Utah, with her little family of four. She gardens, beads, tends to their livestock, and oversees a lab in a local Indian Health Service clinic. But every so often, when she has the chance, she ties up her laces and runs on the landscape that raised her - surrounded by its beauty and protection.

To learn more about Visit with Respect, go to https://bearsearspartnership.org/visit-with-respect

To learn more about Visit with Respect, go to https://bearsearspartnership.org/visit-with-respect

If you want to follow Blaire’s journey, follow her blog, “Shizaad: a Diné woman’s perspective,” to learn more about her stories and experiences.

Photo: Blaire with her husband, Gourdin, and children, Jourdin & Irelynn