During the 1890s, amateur archaeologist Richard Wetherill and his peers excavated roughly 5,000 cultural items associated with the Basketmaker (200 BC-700 AD) and Ancestral Pueblo (700-1300 AD) archaeological cultures. These items were taken from dry caves in the Bears Ears National Monument and Glen Canyon National Recreation Area regions. About 4,000 of these items were perishables, including textiles, baskets, wooden implements, and hide and feather artifacts.

These cultural items are now housed in six museums across the country, and for nearly a century, were overlooked, undocumented, and disconnected from the landscape and cultures from which they were taken.

All of this began to change with the establishment of the Wetherill-Grand Gulch Project, followed by the Cedar Mesa Perishables Project.

The Wetherill-Grand Gulch Project

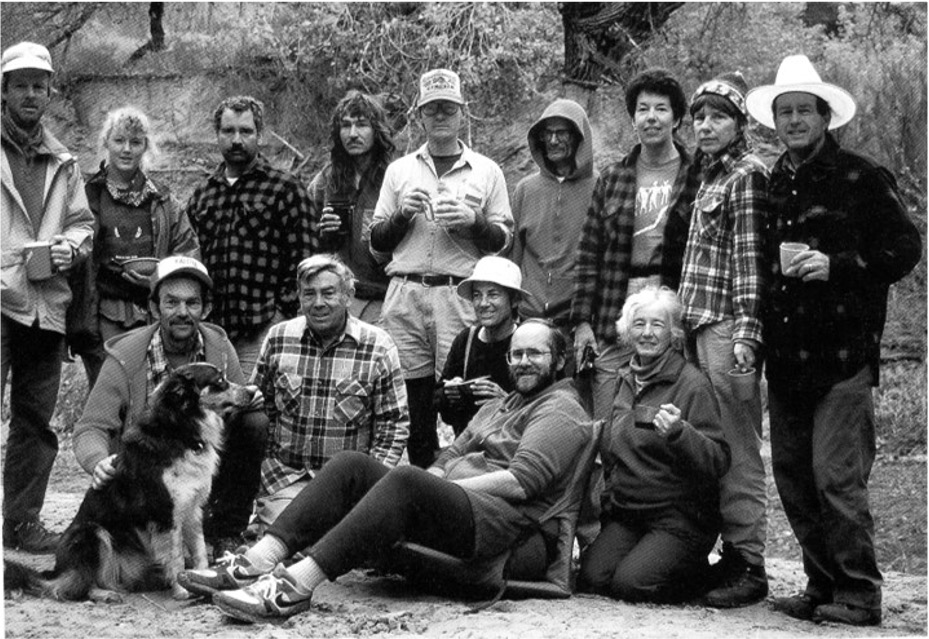

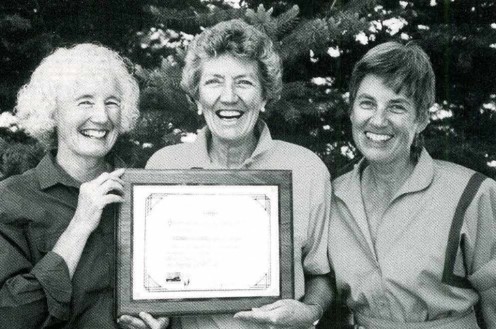

Above: The Wetherill-Grand Gulch Project Team. Below: Ann Phillips, Julia Johnson, and Ann Hays with Julia's Award of Merit from the Utah Humanities Council.

Above: The Wetherill-Grand Gulch Project Team. Below: Ann Phillips, Julia Johnson, and Ann Hays with Julia's Award of Merit from the Utah Humanities Council. In the mid-1980s, a Bureau of Land Management ranger named Fred Blackburn decided to collaborate with a group of canyon backpackers and archaeology buffs to retrace the routes of these early archaeological expeditions. Their goal was to identify the alcoves where these excavations took place, and document the whereabouts of their collections.

In the mid-1980s, a Bureau of Land Management ranger named Fred Blackburn decided to collaborate with a group of canyon backpackers and archaeology buffs to retrace the routes of these early archaeological expeditions. Their goal was to identify the alcoves where these excavations took place, and document the whereabouts of their collections.

The Wetherill-Grand Gulch Project was a first-of-its-kind, interdisciplinary, collaborative endeavor, thanks to the assistance of local outfitter and founding Bears Ears Partnership Board Member Vaughn Hadenfeldt, archaeologist Winston Hurst, photographer Bruce Hucko, archival researchers Ann Phillips and Ann Hayes, the organizational and fiscal support of Julia Johnson, and the moral support of archaeologists Bill Lipe and Joel Janetski.

The newly formed Wetherill-Grand Gulch Project used a “reverse anthropology” strategy to trace the items in these museum collections back to their original site locations. As described in a 2017 American Archaeology magazine article, they used the field journals and maps that survived the initial excavations. They also relied heavily on the rock and wood inscriptions found on their field trips, left by Wetherill and his peers.

At a recent Bears Ears Education Center presentation, Blackburn further explained: “We were piecing together where [the artifacts] came from - it evolved from looking backwards from the museums to the alcoves…This was an impossible task to complete without collaboration.”

The Cedar Mesa Perishables Project

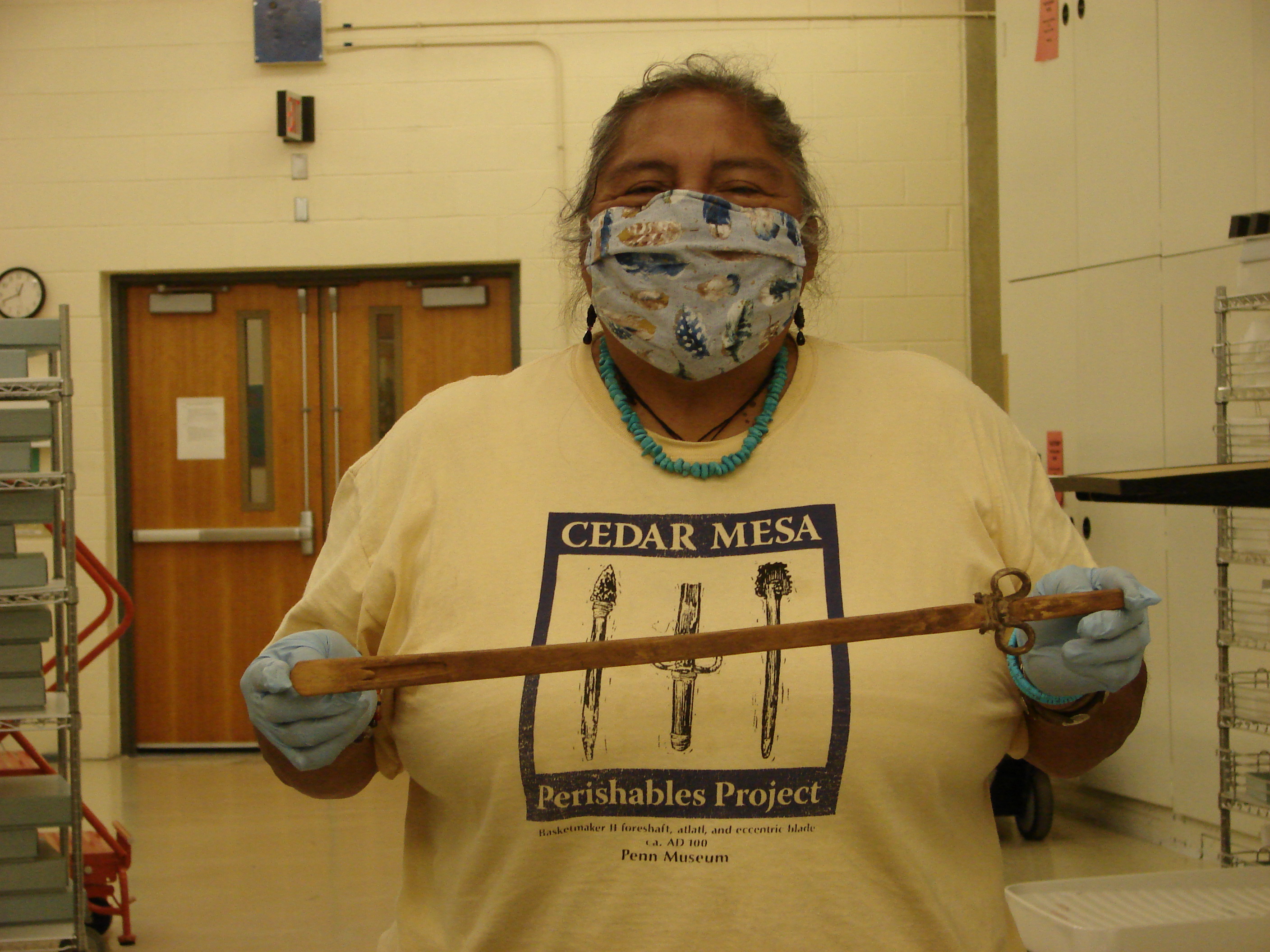

Building upon the foundation laid by the Wetherill-Grand Gulch Project, archaeologist and textiles specialist, Laurie Webster, established the Cedar Mesa Perishables Project in 2011. Her initial goal was to document the individual perishable artifacts in these collections, housed at six museums across the country.

Over the years, the team quickly grew in numbers and diversity of experience. First, Erin Gearty, an anthropology M.A. student at Northern Arizona University, joined the team, followed shortly thereafter by Chuck LaRue, who became the lead analyst of the wood, fur, hide, and feather artifacts. A few years later, the research team expanded to include three Indigenous members: Tiwa-Piro Pueblo weaver Louie Garcia, Zuni fiber artist, and Bears Ears Partnership Board Member, Chris Lewis, and Santa Clara Pueblo/Comanche archaeologist and perishables specialist, Mary Weahkee. Louie, Chris, and Mary serve as perishables experts and the cultural specialists for the project. Like the collaborative make-up of the Wetherill-Grand Gulch Project team, the diverse wealth of knowledge brought to the table by each Cedar Mesa Perishables Project team member has greatly enriched the research.

Over the years, the team quickly grew in numbers and diversity of experience. First, Erin Gearty, an anthropology M.A. student at Northern Arizona University, joined the team, followed shortly thereafter by Chuck LaRue, who became the lead analyst of the wood, fur, hide, and feather artifacts. A few years later, the research team expanded to include three Indigenous members: Tiwa-Piro Pueblo weaver Louie Garcia, Zuni fiber artist, and Bears Ears Partnership Board Member, Chris Lewis, and Santa Clara Pueblo/Comanche archaeologist and perishables specialist, Mary Weahkee. Louie, Chris, and Mary serve as perishables experts and the cultural specialists for the project. Like the collaborative make-up of the Wetherill-Grand Gulch Project team, the diverse wealth of knowledge brought to the table by each Cedar Mesa Perishables Project team member has greatly enriched the research.

Together, the team has traveled to museums to record information about these remarkable collections and raise public awareness of their existence. As Laurie explains, “None of the collectors who excavated this material are around to talk to anymore, so I think of our work as re-excavating collections. We’re basically practicing archaeology in basements.”

In addition to documenting more than 4,000 perishable cultural items, the Cedar Mesa Perishables Project has also conducted specialized analyses. It recently radiocarbon-dated more than 100 sandals, textiles, baskets, wooden implements, and hides from the Bears Ears region, with results ranging from 6500 BC (a sandal) to the late AD 1200s. The project also hired a fiber expert to identify the white animal hair in several textile artifacts, confirming that between 200 BC and AD 900, people used white dog hair in textile production and probably intentionally bred white long-haired dogs for that very purpose.

Indigenous Knowledge & Western Archaeology

Part of what makes the Cedar Mesa Perishables Project so special is the precedent the team has set for Indigenous engagement and leadership in both archaeology and historic preservation. Recognizing that Indigenous and Western-trained scholars bring different priorities and world views to their work, the project has infused Western archaeological interpretations with Indigenous Knowledge and ethical perspectives.

As expressed by team member Louie Garcia in the documentary, Languages of the Landscape: The Cedar Mesa Perishables Project, “We hit it off and had this common interest and passion for these collections and the art. It just set everything up for this amazing synergism that we were able to share our professional knowledge and cultural knowledge to complement each other.”

Traditional Knowledge has informed not only the documentation process, but also brought new perspectives to the research experience. As team member Chris Lewis explained in the same documentary, “Everything you’re working on - inanimate objects - still has a life, still has a soul because it was a plant. The plant is still in it, so you need to acknowledge it.”

The project has also reconnected Indigenous members of the team with cultural practices with which they share an ancestral connection.

“To see the same materials I work with almost on a daily basis such as cotton and yucca in the ancient artifacts makes me feel connected to my Pueblo ancestors,” says Louie. “For us as Pueblo people, the artifacts in these collections have life and a spirit, as our ancestors fashioned each item for a particular purpose from everyday utilitarian use to ceremonial and religious use, many of which are immediately recognizable to me, and others that are not.”

One of the goals of the Cedar Mesa Perishables Project is to make this research widely available, especially to Indigenous Tribes and Pueblos.

At a recent Bears Ears Education Center presentation, team member Mary Weahkee spoke to the impact she has witnessed: “Having seen grandparents that were caught up in the boarding school mentality, losing all that knowledge…By being allowed to go into those collections, we are able to bring them back to those communities, and they are so grateful.”

Changes in the archaeological field are imminent. “I envision the future roles of Western-trained archaeologists as transitioning from ‘experts’ to facilitators and advisors as collaborative projects become more the norm,” says Laurie. “In the case of our project, my decades of work with museum collections and fundraising created the opportunity for three accomplished Pueblo textile and basketry scholars to access their ancestral collections from the Bears Ears area, now housed in expensive cities. Similar collaborations are coming.”

Chuck LaRue and Louie Garcia examining a cotton spindle from , American Museum of Natural History, 2017.

Chuck LaRue and Louie Garcia examining a cotton spindle from , American Museum of Natural History, 2017. What’s Next?

The Cedar Mesa Perishables Project completed its documentation work at six museums in 2022. Now, it is processing the photographs and data to make them accessible to archaeologists, the general public, and Indigenous communities to reinforce ancestral cultural connections to the Bears Ears area. Eventually, the project hopes to reunite these dispersed collections into a single, searchable digital archive.

The final product - also contributing to accessibility - will be a multivocal book that interprets a selection of these perishable items from diverse cultural perspectives.

Support the Cedar Mesa Perishables Project

With the financial sponsorship of Bears Ears Partnership, the Cedar Mesa Perishables Project has already raised more than $23,00 in private donations, which it used for its radiocarbon dating project. With a large Federal grant on the horizon, your support is vital to the continuation of the Cedar Mesa Perishables Project’s important work.

To learn more about the Cedar Mesa Perishables Project and to support their work, visit https://bearsearspartnership.org/donate-to-perishables-project.

And to watch the recent Bears Ears Education Center presentation, “An Evening with the Wetherill-Grand Gulch and Cedar Mesa Perishables Project,” visit https://bearsearspartnership.org/events/event-recordings.

Want to Learn More?

Blackburn, Fred, and Ray A. Williamson. 1997 Cowboys & Cave Dwellers: Basketmaker Archaeology in Utah’s Grand Gulch. School of American Research Press, Santa Fe.

Curtis, Wayne. 2017 Reexcavating the Collections. American Archaeology 20(4):12-19. Spring.

Languages of the Landscape: The Cedar Mesa Perishables Project, Cloudy Ridge Productions. https://cloudyridgeproductions.com/ (scroll down to the film).

Weaving a Partnership: The Collaborative Journey of the Cedar Mesa Perishables Project, Archaeology Café. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_N4qRzG8o-E.

Cedar Mesa Perishables Project: Bringing Life to a Forgotten Archaeological Collection. https://vimeo.com/824774592?share=copy